Call for articles - Literature, Slavery and the Emotions

Literature associated with slavery provokes and often seeks to provoke emotional responses. This has been most widely studied in the context of late 18th and 19th sentimentalism, a key dimension of abolitionist movements. As a first major case of affective politics, slavery paved the way for more recent efforts to not only ‘harness’ emotional responses to human rights abuses but also train subjects to experience them. But emotionality did not enter discourses on slavery for the first time with the rise of abolitionist movements. It is present in early modern and Enlightenment genres such as atrocity stories, travel narratives, autobiographical and anthropological reports, dramas and songs, just as it is found today in a wide spectrum of literary genres ranging from historical novels, political drama and poetry to movies, blogs, life-stories, autofiction and media campaigns against twenty-first slavery. This book examines sentimental responses to slavery across national, historical and linguistic contexts. It also widens the angle of enquiry to encompass other emotions. How has literature, broadly defined, approached the relation between slavery and fear, anger or even happiness and humor? One of the premises of this study is that feelings are never transparent. They are immersed in cultural normativity and politics. In the Western tradition, feeling has often been opposed to reason. Feelings have also been accorded different values, for instance cultivated and non-cultivated, private and public, noble and base. Feelings are deeply related to the power structure of a society. As Sara Ahmed observes, emotions are not beyond social meaning but a form of meaning-making (Ahmed, 2000). Recent interventions in the history and anthropology of emotions have put pressure on established emotional categories, drawing attention to “minor emotions” and to the less stable terrain of affects. In this book, we ask what kinds of work emotions perform in texts about slavery. Since emotions are attuned to social realities, how do they change and adapt to different political and historical contexts? What k genres, tropes, and images evoke emotions in relation to slavery in different literary historical periods? And how is emotionality related t personal life stories, family structures and issues such as gender and race? Understandings of emotionality differ from estimating them to be of no importance at all to ‘real life problems’ (Herbert Ross Brown), damaging for the development of democratic societies (Jean-Jacques Rousseau) to being the exact opposite: a key element in the development of modern democracy and the development of human rights (Lynn Hunt). Critical discussions of the relationship between slavery and emotions have shown that in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, at the peak of the sentimental novel and romanticism, the European and American abolitionist movements produced sentimental accounts and images of enslavement in order to advocate for the abolition, either of the Atlantic slave trade or of slavery itself. (e,g, Lynn Festa (2006), Christopher Brown (2006), Hunt (2007), Christopher Miller (2007). However, it can be asked whether sentimentality in fact contributed significantly to the wave of abolitions that stretched from 1794 to 1888, or whether economic and political factors were more decisive (e.g. Madeleine Dobie (2010)? Is the main function, or effect of emotions in this context positive, e.g. do they promote recognition of slaves as subjects or as agents, or do they elicit pity for them as victims? What kind of psychological investment is asked of the reader/spectator? Questions about the role of emotion in social and political activism continue to reverberate in recent arguments about the strategies and rhetoric of contemporary human rights campaigns. Scholars including Samuel Moyn (2012), Joseph Massad (2008), Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman (2009) and Lilie Chouliaraki (2012) have raised questions about the political moorings of humanitarianism and human rights discourses, connecting them in various ways to the cultivation of pity for or identification with psychological as well as physical suffering. This body of thought intersects with recent developments in the areas of affect theory and the history of emotions. Scholars including Lauren Berlant (1999, 2011) Wendy Brown (1998), Jodi Dean (2010) and Ahmed (2011), have explored the categories of sentiment, emotion, feeling and affect, connecting these disparate concepts to modes of representation and moral and political regimes. The broad goal of this book is to reopen the scholarly conversation relative to literature and slavery to address new work on the use and function of emotion, feeling, affect and sentiment. Looking beyond the category of sentimentalism, the contributions may consider the many different ways in which emotion has been cultivated, projected and normativized in representations of slavery. Please send a 300-word abstract to Karen-Margrethe Simonsen (litkms@cc.au.dk) or Mads Anders Baggesgaard madsbaggesgaard@cc.au.dk no later than July 1, 2017. If selected, a final deadline for the article will be February 1, 2018. All contributions will be submitted for peer review. Selected articles will be published in the three-volume book Comparative Literary Histories of Slavery, eds. Mads Anders Baggesgaard, Madeleine Dobie and Karen-Margrethe Simonsen in the series of literary histories made by CHLEL (Coordinating Committee for Literatures in European Languages) under the ICLA (International Comparative Literature Associatioin) Publishing House: John Benjamins Publishing. Mads Anders Baggesgaard Madeleine Dobie Karen-Margrethe Simonsen

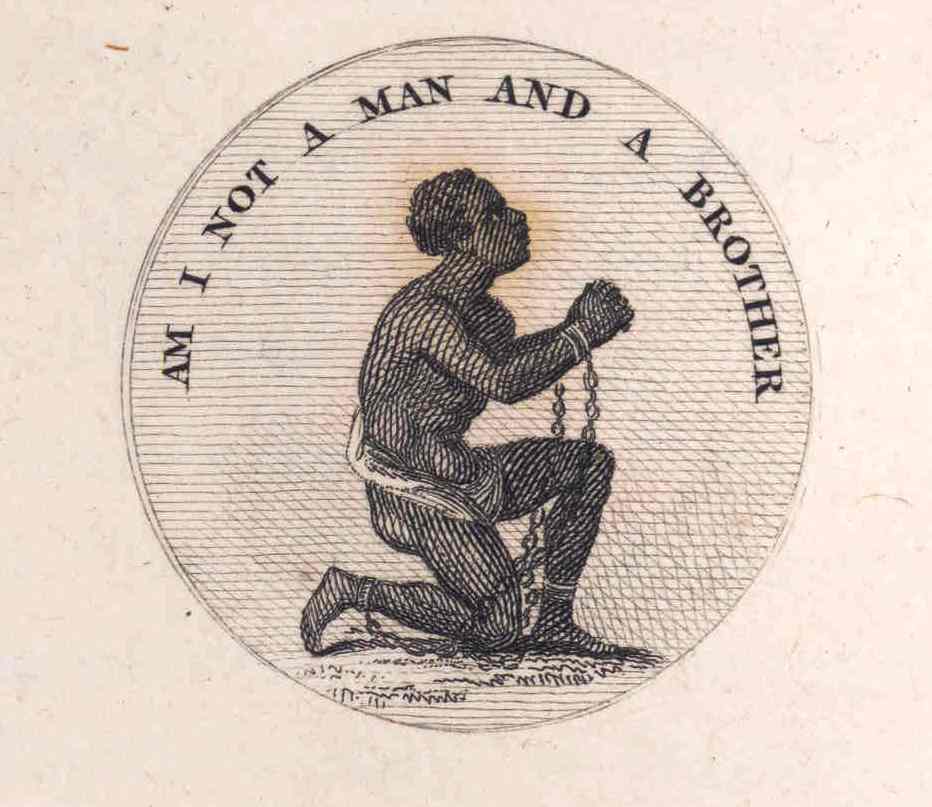

Literature associated with slavery provokes and often seeks to provoke emotional responses. This has been most widely studied in the context of late 18th and 19th sentimentalism, a key dimension of abolitionist movements. As a first major case of affective politics, slavery paved the way for more recent efforts to not only ‘harness’ emotional responses to human rights abuses but also train subjects to experience them.

But emotionality did not enter discourses on slavery for the first time with the rise of abolitionist movements. It is present in early modern and Enlightenment genres such as atrocity stories, travel narratives, autobiographical and anthropological reports, dramas and songs, just as it is found today in a wide spectrum of literary genres ranging from historical novels, political drama and poetry to movies, blogs, life-stories, autofiction and media campaigns against twenty-first slavery.

This book examines sentimental responses to slavery across national, historical and linguistic contexts. It also widens the angle of enquiry to encompass other emotions. How has literature, broadly defined, approached the relation between slavery and fear, anger or even happiness and humor? One of the premises of this study is that feelings are never transparent. They are immersed in cultural normativity and politics. In the Western tradition, feeling has often been opposed to reason. Feelings have also been accorded different values, for instance cultivated and non-cultivated, private and public, noble and base. Feelings are deeply related to the power structure of a society. As Sara Ahmed observes, emotions are not beyond social meaning but a form of meaning-making (Ahmed, 2000). Recent interventions in the history and anthropology of emotions have put pressure on established emotional categories, drawing attention to “minor emotions” and to the less stable terrain of affects.

In this book, we ask what kinds of work emotions perform in texts about slavery. Since emotions are attuned to social realities, how do they change and adapt to different political and historical contexts? What k genres, tropes, and images evoke emotions in relation to slavery in different literary historical periods? And how is emotionality related t personal life stories, family structures and issues such as gender and race?

Understandings of emotionality differ from estimating them to be of no importance at all to ‘real life problems’ (Herbert Ross Brown), damaging for the development of democratic societies (Jean-Jacques Rousseau) to being the exact opposite: a key element in the development of modern democracy and the development of human rights (Lynn Hunt). Critical discussions of the relationship between slavery and emotions have shown that in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, at the peak of the sentimental novel and romanticism, the European and American abolitionist movements produced sentimental accounts and images of enslavement in order to advocate for the abolition, either of the Atlantic slave trade or of slavery itself. (e,g, Lynn Festa (2006), Christopher Brown (2006), Hunt (2007), Christopher Miller (2007). However, it can be asked whether sentimentality in fact contributed significantly to the wave of abolitions that stretched from 1794 to 1888, or whether economic and political factors were more decisive (e.g. Madeleine Dobie (2010)? Is the main function, or effect of emotions in this context positive, e.g. do they promote recognition of slaves as subjects or as agents, or do they elicit pity for them as victims? What kind of psychological investment is asked of the reader/spectator?

Questions about the role of emotion in social and political activism continue to reverberate in recent arguments about the strategies and rhetoric of contemporary human rights campaigns. Scholars including Samuel Moyn (2012), Joseph Massad (2008), Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman (2009) and Lilie Chouliaraki (2012) have raised questions about the political moorings of humanitarianism and human rights discourses, connecting them in various ways to the cultivation of pity for or identification with psychological as well as physical suffering. This body of thought intersects with recent developments in the areas of affect theory and the history of emotions. Scholars including Lauren Berlant (1999, 2011) Wendy Brown (1998), Jodi Dean (2010) and Ahmed (2011), have explored the categories of sentiment, emotion, feeling and affect, connecting these disparate concepts to modes of representation and moral and political regimes.

The broad goal of this book is to reopen the scholarly conversation relative to literature and slavery to address new work on the use and function of emotion, feeling, affect and sentiment. Looking beyond the category of sentimentalism, the contributions may consider the many different ways in which emotion has been cultivated, projected and normativized in representations of slavery.

Please send a 300-word abstract to Karen-Margrethe Simonsen (litkms@cc.au.dk) or Mads Anders Baggesgaard madsbaggesgaard@cc.au.dk no later than August 15, 2017.

If selected, a final deadline for the article will be March 15, 2018. All contributions will be submitted for peer review.

Selected articles will be published in the three-volume book Comparative Literary Histories of Slavery, eds. Mads Anders Baggesgaard, Madeleine Dobie and Karen-Margrethe Simonsen in the series of literary histories made by CHLEL (Coordinating Committee for Literatures in European Languages) under the ICLA (International Comparative Literature Associatioin) Publishing House: John Benjamins Publishing.

Mads Anders Baggesgaard

Madeleine Dobie

Karen-Margrethe Simonsen